PROSE

BUBI

PROSE

| In my family's dialect of Yiddish, "Bubi" means "grandmother," and it's what every kid in the neighbourhood called her--because she was their Bubi, too. When she'd come to stay with us (which she did often), she used to bring packages of gum not just for her grandchildren, but for everyone. She'd tell us stories of Europe, and of when she moved to America, arriving here as a girl of 19 on "August the eighth, 1921"...but not before she'd seen the boulevards of Prague and Vienna, and not before she, the eldest of nine, had swept dirt floors to make them clean for her little brothers and sisters. |

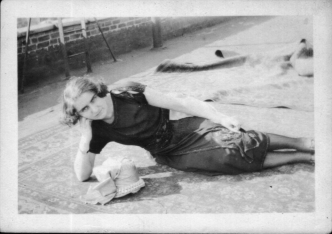

| She was born Sheyndl Steinhart--and remained so all her life, having married her second cousin Hersh. "Sheyndl" means "beautiful one," and she was--a tall strawberry blonde with wide Slavic features, a peaches-and-cream complexion, and black lashes over China blue eyes. (Her English name, Sylvia, never quite did her justice.) I have a picture of her vamping on a New York City rooftop, in a flapper dress modified into modesty. Even 70-something years later, it draws attention; it sits on the shelf above my computer, where I can always look over to it for a quick smile. |

|

| Bubi spent the last thirty years of her life in near-total darkness.

She started losing her sight in the 1950's, and by the time I was about

2, she could only see a few shadows, like the ones made by the hands on

the clock on the oven. "It's 4:00, right, Chaneleh?" she'd say to

me."Time to watch Edge of Night." Despite the considerable inconvenience

of her inability to see, she never stopped cooking or cleaning or going

into the street to go shopping or fussing over my grandfather--who was

the sort of guy who'd deign to lift his legs so you could vacuum under

them. (But they were a handsome couple; he was as fair as she was ruddy,

with black hair and piercing dark eyes.)

We tried one last-gasp attempt in 1968, a cornea transplant--I was ten, so I was allowed to visit her in the hospital--and while she actually saw better shadows for a little while, she plunged back into total blindness not long after. But she never gave up. Ever. She folded bills in her wallet with different kinds of corners, so she always knew exactly how much money she had, and which denominations. She cooked and baked-- feeling how high the flame was on the stove by lowering her hand until she could tell it was right, feeling for the notches on the temperature control on the oven, and feeling to make sure she had the "chickie" cookie cutter, her grandchildren's favourite. She knew by touch every garment she owned, and if a button fell off, she'd just get confirmation from one of us that the blue thread, the dark blue, was the third bobbin from the right, yes? And she and my mother and I sang our way to Toronto, a ten-hour trip in 1964, without repeating ourselves once. In fact, she took special pleasure in knowing that a song she had learned in Russian as a small girl was sung in Yiddish by her daughter, and in Hebrew by her oldest granddaughter. I always loved when I could make Bubi smile! |

Bubi & Zaydi, mid-1920's |

And just when you thought there were no more surprises left, you'd

get one. One did not call Bubi between 7 and 8 on Sunday night, because

she did not like missing 60 Minutes. And she listened to news/talk

stations during the day, so she was always well-informed on most matters

of importance. My sister Ellen loves to tell how Bubi--purely out of curiosity,

because while none of Bubi's friends were gay, she knew Ellen had gay friends--well,

she wanted to know exactly what it was that people whose sexual orientation

differed from hers...did! It was something she thought she should know,

so she asked.

A moment that still makes me smile is about ten years old. One afternoon just before I left WNEW, Mom was taking Bubi to the doctor and she had the radio on in the car as Jim Harlan spoke between songs. Harlan said, "And now it's time for our Mets Update." Bubi heard my voice, and shrieked, "That's Chaneleh on the radio!" My mother said, "Yes, Mama." And Bubi said, "Shhhh. I want to hear." After my five minute rundown of the National League, Bubi gave a sigh and said, "You know, I didn't understand a single word she said...but didn't she say it beautiful?" |

| And where am I going with this?

Bubi was forever thanking people. "Thank you for coming over to talk with me," if she was out taking some sun. "Thank you for saying hi." "Thank you for remembering me." In someone else, it might have been cloying. In Bubi, you knew it was honest appreciation...and it was so ingrained, that at the end, in the hospital, even when she couldn't recognise who anyone was, if someone smoothed her pillow or straightened out the IV, it was immediately followed by a "thank you." I just couldn't stand to watch her deteriorate, something about which I'll feel guilty until the day I die. That, and that I never did learn how to play her favourite piano piece, "Malaguena"...and that I never gave her the chance to fulfill her promise to dance at my wedding. As things were getting worse and worse, I'd bury myself in work and find every reason not to go, because I just couldn't watch. And it was especially bad, because I was the one who was closest...the one who used to call every Friday night before the Sabbath from school or from my office, the one who knew all the old songs, the one who kept the family history. |

| One day in late June, 1990, my mother said to me, "It's almost over.

Do you really think you'll ever have any peace if you don't say goodbye?"

And so I went over to the hospital with Mom. Bubi looked so frail; her

expression was completely blank. And I, whom she had trouble hearing under

the best of circumstances (she used to call me her little mouse...when

she wasn't calling me ketzeleh, "little kitten"), said, "Hello,

Bubi." I didn't think I'd got through--it didn't look like she'd heard

me. But then her hand came out from under the covers, and went around my

wrist--that's how she always told me from my sisters; I'm the oldest, but

the smallest--and she said, "You're a good little pussycat."

Those were the last words I ever heard my grandmother say. And so, every day, I try to bring a little bit of Bubi to wherever I go. I make a point of thanking people. I listen to their problems, and try to offer encouragement. I try not to take myself too seriously, and remember that rich or poor, I'm still the same person. (My grandparents were wealthy people until the late 1940's; then they lost everything. The closest I ever heard Bubi come to complaining was one of her shprikhverter, proverbs: "Remember, rich or poor, it's always good to have money!") Isn't it a lovely tribute to this magnificent but completely unprepossessing woman, that complete strangers invoke her name? Over the years, the guys at Z-100, and the guys at the ballpark, and the guys at SJS had heard my Bubi-isms so often, that they would start to use them, too! (The proper punchline to every joke of merit is "Daht vuz a good vun!") How lucky am I, that I get to share the person who most exemplified the word "lady"--in every sense of that overused word--with the entire rest of the world? |

|

| And if she knew I'd spent almost an hour-and-a-half sitting here writing this, she'd say, "Yeah, surrrre. Bubi, shubi! Now go to bed, ketzeleh. It's late. But thank you for remembering me." |

First, you tell yourself it didn't really happen.

But when it keeps haunting your days and nights, creeping into your consciousness every chance it gets, you have to re-consider.

Then you tell yourself, okay, something happened, but it's not as bad as you'd thought it was.

But when your internal VCR keeps replaying the scene over and over in the same chilling detail, you are forced to deal with the fact that yes, something happened--and it's every bit as bad as you'd thought it was.

So you tell yourself forget it...because when it comes right down to it, it's your word against his--and he's the boss and you're not. Because the people in charge are men, and you have no reason to believe they would find anything out of the ordinary. Because times are tight and jobs are not that easy to come by. Because you're a woman in a man's field, and if you're going to make it, you've got to prove you can take what the guys dish out.

Because nothing you learned in school or from your mother ever prepares you for the Saturday morning on which a superior calls you into a room for some help with a problem, and the next thing you know, his pants are around his ankles and his arm is tight around your waist. And he's at least twice your size and strength, the walls are soundproof, and the door is locked.

By the grace of a merciful God and some very quick thinking, you talk your way out of it before his obvious intention becomes a reality. Afterwards, you have to know, so you ask if you've done anything to provoke this behavior. He says no. Physically, you're just shaken up; your mind and soul, however, feel violated.

Externally, the reaction is subtle. You hack off your long hair. You gain some weight. You take to wearing a lot of grey, forgetting that you ever owned anything red. And you can't explain why you start to shake every time circumstance brings you into that room.

Embarrassment, shame, and confusion prevent you from telling your mother or your sisters or your friends...and you certainly can't tell anyone at work.

It doesn't sound all that different from the reaction to any attack of a sexual nature (which, of course, is about power, not sex), but it is. From the beginning of time, people have used work to escape from their personal lives, and life to escape from their jobs--but this is both, and there is no escape.

See, here you thought you were getting all this approval and admiration because you were doing a good job and were on your way to the advancement you sought in your chosen profession--and it turns out that it was just a guy trying to get into your skirt. Which, in your poor embattled brain, means that you weren't good enough after all. And you're never going to be good enough.

So everyone wonders why you keep working harder than ever but shrink from recognition, why every time you make a mistake you act as if it were a knife in your gut, why you can't stand up for yourself. Why someone standing behind you while you're sitting at your desk is enough to make you jump. Why the smell of a certain soap or the sound of a certain voice on TV will make you cringe, visibly and involuntarily.

Why this feeling of unworthiness follows you, even a couple of jobs later in a completely different field. (Ironically, it's one in which sexism is rumored to run rampant but actually is the only one in which you've been treated for the most part with fairness.) Even you wonder.Your self-disgust increases daily. More proof that you're not good enough--neither to do the job nor to overcome your past.

And then a case of sexual harassment comes to public notice, and women who have never been there come out of the woodwork, insisting that no self-respecting woman would take that kind of thing.

But what they don't understand is, that kind of thing robs you of your self-respect, not to mention your faith in your own judgment. So you take it. And you keep on taking it until with any luck, either by yourself or with some help, your shattered confidence is gradually rebuilt and you allow yourself to think that perhaps you might be good enough after all.

So you go after your dream once more, somewhat sadder and a lot stronger.

And then maybe you let your hair grow again, and think about buying a red

dress.

Now that it's intersession and you've all passed Baseball 101A (Regular Season) and 101B (Post-Season) with flying colors, here's your chance to get a head start on some of your fellow students who are vegetating between semesters. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Baseball 200, Introduction to Fundamental Truths and Pet Peeves. In this segment, we will cover some of the profundities, problems, and peculiarities of pitching. Let us begin.

1. The split-finger fastball and the forkball are not identical twins; they're fraternal. They may look a lot alike, but, despite rumors to the contrary, they are not the same pitch. The forkball is choked all the way back in the hand, with the fingers splayed at maximum or near-max separation. The typical splitter is held a little further forward in the hand, with the position of the fingers spread so that they split the difference between the traditional fastball and forkball grips. (A real forkball requires a large hand.)

A truly nasty splitter is thrown hard and looks like a fastball until the last possible second, when it abruptly drops into the dirt just as your bat is slicing a few feet above. The forkball has a similar action, but tends to be used as more of a change-of-pace. The one thing a pitcher does not want to do with either one of these pitches is hang it, because by starting out high, the ball's dive is directly into the strike zone--and, to paraphrase former hurler and current scribe Jim Brosnan, "He who hangs too many, soon hangs up his glove forever."That concludes our lesson for today. Be sure to return tomorrow, when we tackle the topic of "Fielding Follies" ("You Can't Always Catch The Ball If You Never Move Your Feet").2. The slider was the pitch of the '60's and part of the '70's; the split-finger fastball has been the pitch of the '80's. Now it's time to get ready for the pitch of the '90's: the change-up. It's not sexy like the splitter, it doesn't have the allure or pizazz of high heat, and it definitely lacks the majesty of the classic curveball--but it works. Phillies manager Nick Leyva says, "The change-up, when it's a good one and used right, is the toughest pitch to hit." And Mets announcer Gary Cohen adds, "Guys like Bobby Ojeda, who can change speeds like that, can pitch successfully until they're 50!"

3. Those bases on balls really do hurt as much as everyone says they do. If Dennis Eckersley hadn't walked Mike Davis in the ninth inning of Game 1 of the 1988 World Series, Kirk Gibson would never have even come up to bat, let alone hit a homer to hand LA a 5-4 win. It was a textbook case of "deja vu all over again," since the Dodgers had pulled out an analogous win in Game 4 of the National League playoffs, when Dwight Gooden (despite having him at an 0-2 advantage) gave John Shelby a free pass to lead off the ninth...after which Mike Scioscia sent Gooden's next pitch over the right field fence to tie the game at 4-4. This set the stage for Gibson to hit one out in the twelfth, giving the Dodgers a victory by the same 5-4 score.

Eckersley, by the way, learned his lesson. In 57.2 innings pitched during the '89 season, he issued precisely three (3) walks.

4. It is not always fair to evaluate a pitcher's performance on the basis of his won-lost record. In 1968, the year he established a modern National League ERA mark (1.12), Bob Gibson started the season 3-5, with two no-decisions! (Tim McCarver, who caught most of Gibson's starts, maintains, "The way he pitched all season, to this day I can't figure out how he lost nine games.") In 1989, three of 1988's big winners (among others) struggled for victories: Orel Hershiser went 15-15 despite a nearly league-leading 2.31 ERA; Ron Darling finished up 14-14 by losing eight games in which he surrendered three earned runs or fewer; and Tim Leary was winless in his last five starts (despite a 2.18 ERA in that span) to end up 8-14.

On the other hand, there's Oakland's Storm Davis, who just narrowly missed a coveted 20-win season (he went 19-7) despite 187 hits and 68 walks surrendered in 169.1 innings pitched, to go with a hefty 4.36 ERA.

The keys are run support and defense. There's an old Yiddish proverb that says, "In a restaurant, choose a table near the waiter." If you're a pitcher, it's wise to time your starts for when your teammates are hitting what the other team throws and catching what the other team hits.

My dad and I started college

at the same time; he was 47, I was 17. One night during spring break on

my campus, Dad took me with him to his English Composition course--where

the assignment was to compose an essay on the piece of fruit sitting atop

the professor's desk, with special attention to use of the senses.--AB

The lemon is a roundish yellow fruit with a brown core stem on the bottom and a sort of nose on the top. It is a cousin to the etrog, but that is another story entirely. Also, the common everyday lemon usually has a green "Sunkist" stamped on the side.

The outside of a lemon feels relatively smooth and firm. If your lemon has been refrigerated, it will also feel cold. The inside feels soft and squishy, except for the pits. They feel hard and pointy. The inside of a lemon will also feel very sticky if it has been squished too hard.

A lemon's scent is light and citrus-like. It even smells yellow. The scent of a lemon reminds you of Florida, sunshine, fruit groves, and the bathroom after someone has taken a shower.

The taste of a lemon is tart and tangy. They are generally considered good, except for the pits, which do not taste yellow. It has been said that if you wish to improve the taste of your lemon, you should remove the outside before eating the inside and avoid the pits.

Looking at a lemon from an auditory standpoint is purely a subjective matter. I do not know what your lemon tells you, but that which mine tells me is my business and mine alone.

All I will say is that the lemon is a very sensual fruit.